Musings

A Gallery of Tomatoes

A favorite summer ritual is to paint a tomato (or two). Typically, these are little paintings that measure 6” x 8” and are done in oil on canvas or carton.

What Is It about Tomatoes?

At this time of the year, I am happily overwhelmed by tomatoes.

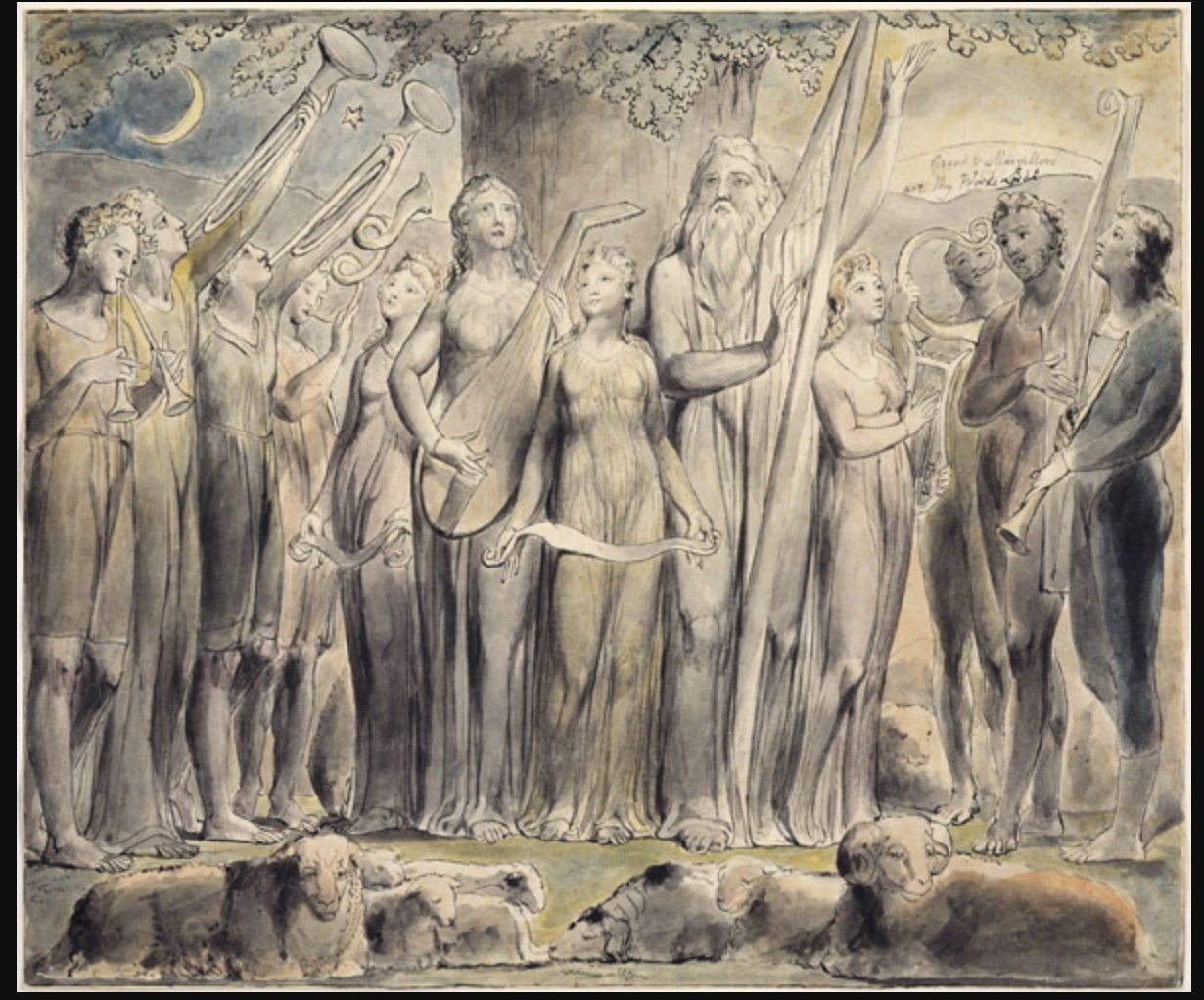

Ralph Vaughan Williams, Job, Blake, et al

When one kind of art comes together with another to create a single piece of work, magic happens. These days, collaborations between poets and painters most frequently get my attention. But last weekend, at the 33rd Bard Music Festival dedicated to Ralph Vaughan Williams, a wonderful mix of music and visual images swept me away.

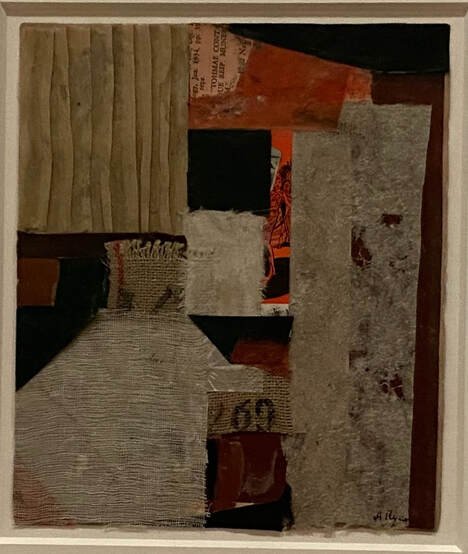

Discovering Gems in the Museum of Modern Art

The last time I was in the city, I headed to the Museum of Modern Art to see the current Georgia O'Keeffe Exhibition (until August 12, 2023), an exhibit that many friends have praised. Unfortunately, the rooms were packed. The crowd was mostly women between the ages of 50 and 75 in long animated conversations in front of the works. Not a good way to see art.

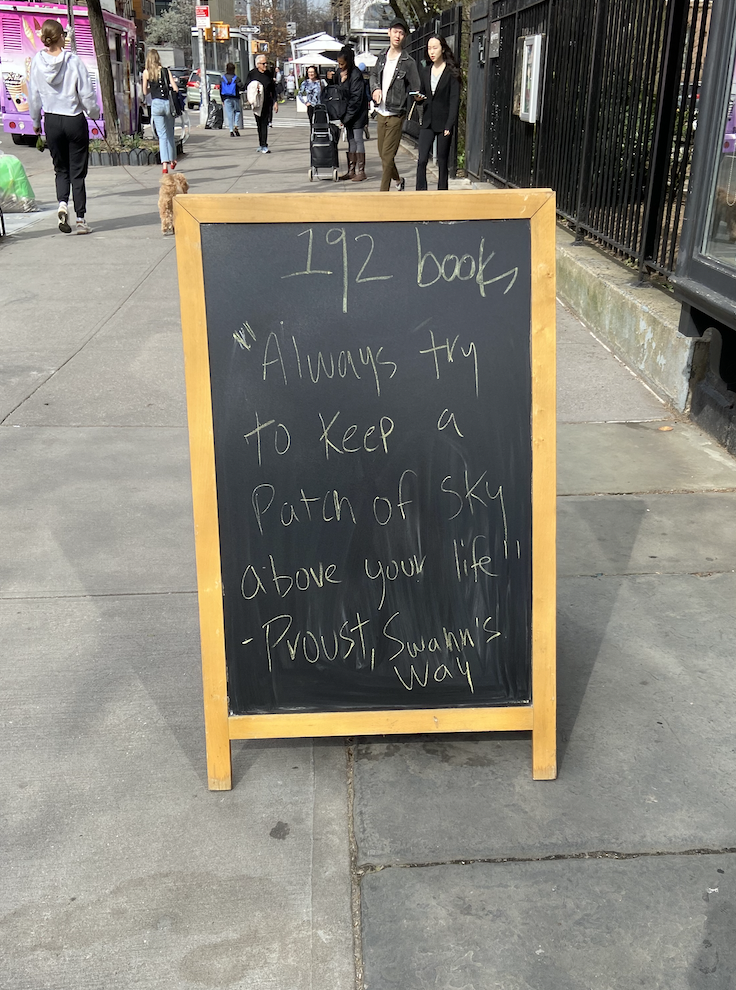

A Little Proust and Then, Some Frankenthaler

The Helen Frankenthaler exhibit, "Drawing within Nature: Paintings from the 1990s," was high on the list of shows I wanted to see after our return from a month in Mexico. Within days of landing, I found myself on the way to the gallery. I knew I was onto a good afternoon when I spotted this board outside the wonderful 10th Avenue store, 192 Books.

A Studio Visit in the Country

Recently, Patrice Wynne, a good friend who lives in San Miguel de Allende and travels to New York, spent some time with us in Pine Plains. She took great photographs of my studio as we talked and caught up with life and each other.

There are long view shots that offer a sense of the larger studio space, up close views of the tools of the trade, studio vignettes that capture objects used in the paintings, and of course, a photo of Ula, the studio dog. I have put these together in a slide show.

Back in the City, Back in Museums: Kandinsky

It is hard to beat this: At the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, sitting with a friend in the third level cafe, looking out the windows and across Central Park to the San Remo building (1930). Nonetheless, it does get better. After eating a bit and talking a lot -- much to catch up, we set out to view two wonderful exhibitions: the grand Kandinsky retrospective, Around the Circle, and a introduction to the paintings of Etel Adnan, Light's New Measure.

Where I Worked When It was Too Cold in 2020/2021

I have been blessed as a painter by having wonderful spaces in which to work, both in the city and in the country. In the city from November to April, for more than the past ten years, I have painted in the studio created by the late Saul Lambert, internationally recognized illustrator and spiritually and physically powerful painter. In the country, from April to November, a painting studio grown out of a sturdy three car garage lifts my mood and inspires me to work every time I step into it. Having a good studio space is really really important. Here are just a few artists' quotations on their connections with their studios:

Painting Cups

A New Yorker writer once described Tommy Tune, the tall song and dance man famous for his showmanship and big, fancy productions on Broadway, as "never having met a costume he didn't like." I feel that way about myself: I never met a cup I didn't like and didn't want to paint.

Pottery has been especially important to me these days, during the pandemic. We spend so much time at home. The objects we have at hand have a solemnity and prominence we didn't always give them when we rushed from home to the outside world. Now, we can savor and linger over that morning coffee and make a slow ritual of tea in the afternoon. Given how much I had come to appreciate these moments with cup in hand over the last several months, it seemed right to bring them into the painting studio and do their portraits.

Music in the Painting Studio

Early in my art training as an adult, I learned an important lesson about listening to music while working. The lesson was provoked by a young woman in the class who was always plugged into some sort of music-playing device. She liked her music loud, so even though she wore headphones, we all got to "enjoy" what she was listening to. Bearing this for a while but reaching his limit by the third class, the teacher told her to unplug. He told us all that we should draw and paint only to our own internal music. Listening to others' music was a dangerous distraction, he said. Radios, tape players, walkmen, etc. were from that day on banned from the class.

Sending Out Poems: The Backstory

One day before the COVID pandemic struck and shut down New York City, we arrived in Mexico, in San Miguel de Allende, for what was to have been our annual month long stay. Given growing health risks in New York, the seemingly lower risk in Mexico, and the generosity of friends, we decided to extend our time. We were in Mexico until early June, nearly two months longer than planned.

Winter: A Very Evocative Season

Along with paintings and photographs, there are many beautiful poems about Winter. Among them are some that go straight to the heart and soul. They bring back wonderful memories and evoke strong yearnings. A few of these are posted here.

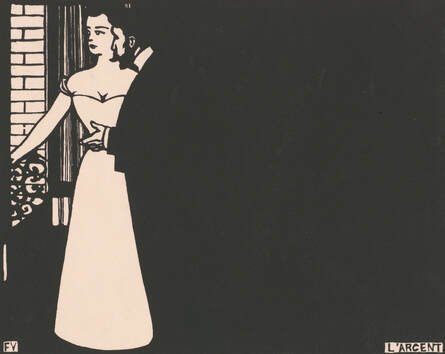

Letting Art Fill in Photography’s Gaps: Images of Sabina Spielrein

As I described in the prior blog post, I am on the lookout for art that will supplement the little photographic evidence we have about Sabina Spielrein. Felix Vallotton (1865-1925), printmaker and painter, is the artist most helpful to me so far in my search for art that expresses Sabina Spielrein (1885-1942) — art that represents something of her way of being in the world. They are contemporaries. While Vallotton makes his art in France, all the following happens for Sabina: She journeys from a troubled childhood in Russia, undergoes treatment for psychiatric symptoms in Switzerland; and, most importantly, establishes an impressive career in psychiatry and psychoanalysis as a scholar and therapist in Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, Geneva, and Moscow. The year of Vallotton’s death coincides with Sabina’s return to Rostov, the Russian city of her birth.

The scene Vallotton gives us in his 1897 woodblock print, Money , from the series he titled, Intimacies, is full of ambiguity. What is going on here and what does it have to do Sabina?

Art Fills Photography’s Gaps: What To Do When There are No Photos of Sabina Spielrein

We live with photographs always at hand. All our media sources are filled with peoples’ pictures, friends and family are constantly sending us pictures of themselves, we have selfies; and, of course, there are Facebook and Instagram images showing us how so many of us look, in so many places, at so many times. It is distressing now when we can’t find an image of another person.

This is a blog about a woman with an exceptionally sparse photographic record and a story of how I tried to make up for that lack by creating an image of her through the art of her time and my own. First, I will write something about who the woman was and then I will share images of paintings and prints that I think show us something about her. The artists who helped me fill out the picture are Felix Vallotton, Ernst Kirchner, and Eri Iwasaki.

All on the Same Afternoon

One afternoon, not so long ago, I encountered three amazing images of women. In each, a woman wears a special head covering. The first came from a posting by my photographer friend, Ulas Tosun. It presents a woman he photographed wearing wonderfully colorful clothing. Hers is the face of an older woman, strong and showing signs of a life lived with determination.

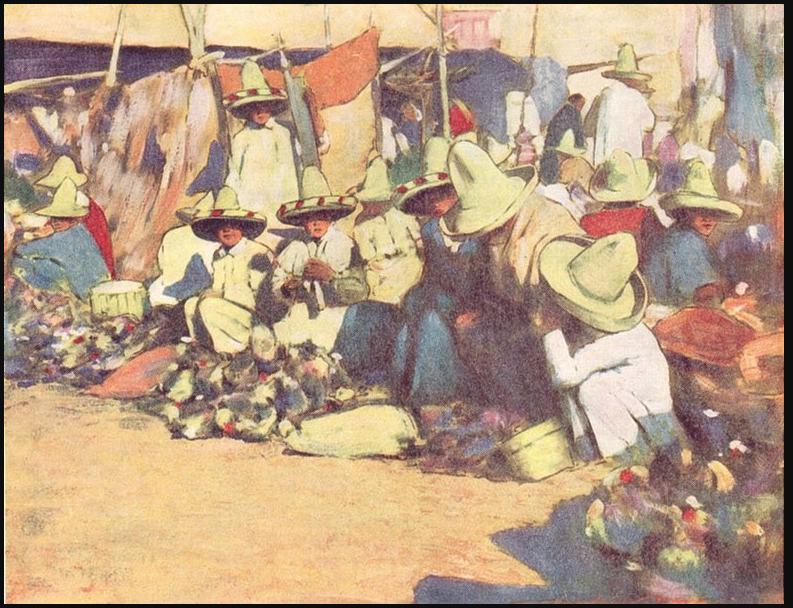

Travel Notes: Oaxaca, Mexico

An art exhibition was not as important in sending us to Oaxaca; as the Derain, Balthus, and Giacometti exhibit was in launching our trip to France. Nonetheless, another museum show did provide a strong second for our decision to travel to a new part of Mexico. Many friends had encouraged us to branch out beyond San Miguel de Allende and spend some time in Oaxaca: "If you like San Miguel, you will love Oaxaca." Friends' words were resoundingly supported at a lovely show at the Yale University Art Gallery last summer, Small-Great Objects: Anni and Josef Albers in the Americas. This was an exhibition of pieces of art that the Albers, an artist couple -- she, an esteemed textile artist; he, an esteemed painter -- had collected in their travels in Mexico and South America. The Albers had loved Mexico, especially Oaxaca, for its art, grand Prehispanic ruins, food, weather, and friends with whom they enjoyed life in a very special way.

From Pine Plains to Paris — It Just Took Jazz!

A Travel Memoir

Plus, comments on:

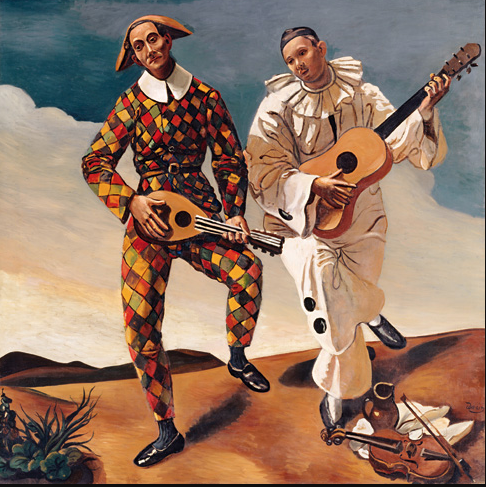

Derain, Balthus, and Giacometti: An Artistic Friendship, MUSEE D’ART MODERNE DE LA VILLE DE PARIS, 2 June – 29 October 2017.

Being Modern: MOMA in Paris. FONDATION LOUIS VUITTON, 11 October 2017 - 5 March 2018.

It was a quiet summer Sunday afternoon in Pine Plains. David had just gone off to jazz camp in Vermont. I settled down for some reading. Sitting in the very comfortable leather chair, with my lovely little dog Ula at my side, I dove into Jed Perl’s very positive review of an exhibition of Derain, Balthus, and Giacometti, at the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris. Click here for a link to that article.

Perl called it "a show packed with ravishments and revelations."

Thinking about Judith Clark

Below, some thoughts inspired by Jim Dwyer’s compelling essay about Judith Clark[1] and her parole board’s recent decision not to grant her parole, after Governor Cuomo granted her clemency. Jim Dwyer, Denied Parole, a Former Radical Reflects on Symbolism and Redemption. New York Times, May 4, 2017, p. A19

A Syrian Boy and a Botticelli Madonna

Ten days before Christmas, 2016, on the front page of the New York Times, Michael Kimmelman warns us that photographs don't have the power they once had. The art critic writes that images don't capture and hold people's attention the ways they once did. They don't provoke people to do something about the horror to which the images bear witness. To support his claim, he compares the public response to two pairs of photographs. The earlier pair shows a starving Sudanese girl in 1993 (Kevin Carter, Getty Images), and children fleeing an accidental South Vietnamese napalm strike in 1972 (Nick Ut, Associated Press).