Letting Art Fill in Photography’s Gaps: Images of Sabina Spielrein

As I described in the prior blog post, I am on the lookout for art that will supplement the little photographic evidence we have about Sabina Spielrein. Felix Vallotton (1865-1925), printmaker and painter, is the artist most helpful to me so far in my search for art that expresses Sabina Spielrein (1885-1942) — art that represents something of her way of being in the world. They are contemporaries. While Vallotton makes his art in France, all the following happens for Sabina: She journeys from a troubled childhood in Russia, undergoes treatment for psychiatric symptoms in Switzerland; and, most importantly, establishes an impressive career in psychiatry and psychoanalysis as a scholar and therapist in Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, Geneva, and Moscow. The year of Vallotton’s death coincides with Sabina’s return to Rostov, the Russian city of her birth.

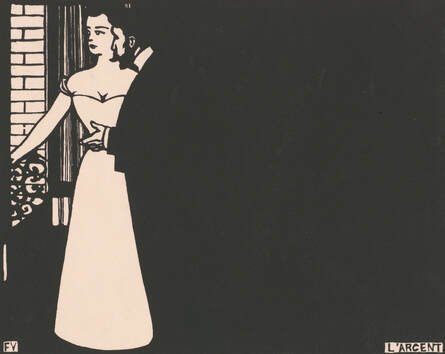

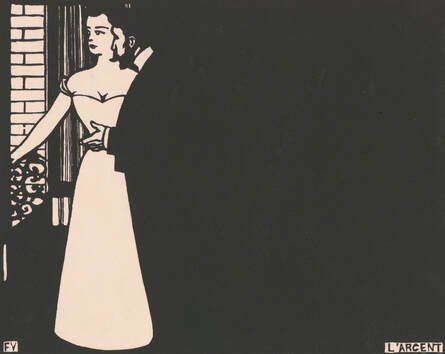

The scene Vallotton gives us in his 1897 woodblock print, Money , from the series he titled, Intimacies, is full of ambiguity. What is going on here and what does it have to do Sabina?

The print invites the viewer to fill in her own explanation of the scene. For me, the woman at the left edge of the print is Sabina. She stands at an open window at the Burgholzli hospital where she was admitted just a few months earlier in a highly anxious state. She is calm now and looks to the light outside. She is perhaps a little apprehensive, but mostly, she is optimistic. She sees a world outside that will provide opportunities to put to good use the brilliance she is sure she possesses. She sees possibilities to actualize the special calling she knows she is destined for.

At the same time that she looks into the light, Sabina looks away from the large mass of darkness to her left (our right). That darkness contains memories of her troubled childhood, including abuse by her father whose love she sought. The darkness also holds those negative ideas and feelings she has long carried about terrible things yet to happen in her life. The window seems a way out of the darkness, yet the darkness encroaches her space.

At the leading edge of the black mass that takes over most of the print is a man. For me, that man is Carl Jung. He engages Sabina in a conversation. Part of that talk may be helpful to her. He stands with Sabina at the window, he may be encouraging her to engage with life and work outside the clinic. Nonetheless, he is an ominous figure. As I look at him, taking over a little too much of Sabina’s space, I cannot help but think of the harm and injustice in his close sensual relationship with Sabina. That happened when she was his young vulnerable patient and he was her older married physician. Sabina writes that she both loved and hated Jung. In her diary and letters, she records many ways he rejected her and sought to limit her possibilities. He is indeed part of the darkness she seeks to escape.

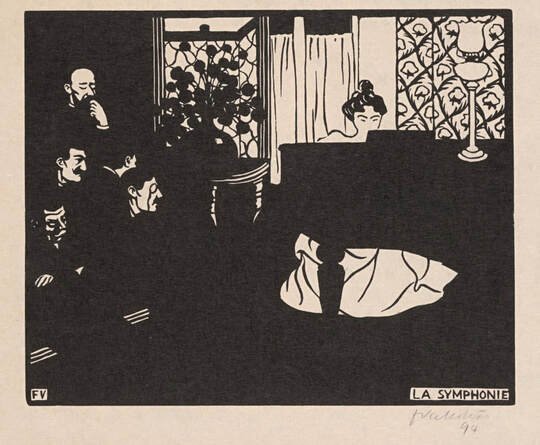

In the second 1897 print, The Symphony, Vallotton shows us a young woman who sits and performs at a grand piano. Half of the print is taken up with her serious playing. At the left are a group of men who look at her and listen. It is an updated Susanna and the Elders image: Older men observe and leer at a beautiful young woman.

For me, the young woman is again Sabina. Although she was a skilled pianist and had a life-long love of music, she was not a concert pianist. Sabina did, however, perform and deliver papers at important psychoanalytic meetings. Just replace the piano with a meeting table or a conference podium. She was often the only or one of the very few women present. For me, the men in the print represent members of Freud’s psychoanalytic circle and other analysts, The men may have asked her to perform/give the lecture, but their response seems mixed. The motley assortment of faces expresses attentive interest but also boredom and anger. At the top of the heap is a man who pulls at his beard with eyes closed (how can one not see Freud in this figure?). The apparent leader is silent. That is as it should be as she plays, but I want him to speak when she finishes. I want him to praise her and to encourage his colleagues to recognize her contributions.

We know that Freud invited Sabina to give a paper to the Vienna psychoanalytic circle early in her career. That was probably one of her first major presentation to the group of specialists, essentially all men. Most of those present were critical of her work, finding it difficult to integrate her unique theories and accept that a “little girl” could make serious contributions. Freud was too distracted to bring some sense and order to their responses. He saw the brilliance in her

paper but was too distracted by fears that her ideas might not support his own to give her the appreciation she was due.

The Vienna episode was one of many times that Sabina’s distinctive ideas and hard work to advance psychoanalysis as a science were dismissed and overlooked by others.

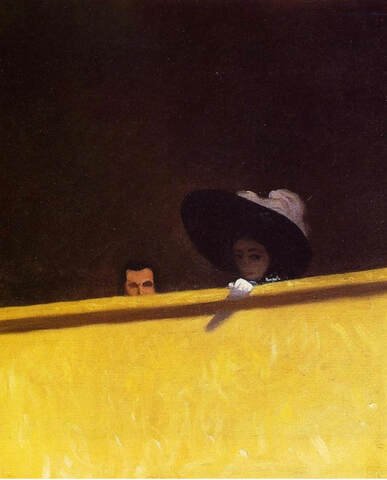

The third Vallotton piece is a 1909 painting titled Box Seats at the Theater: The Gentleman and the Lady. It shares many of the themes offered by the first two works — the ominous man (is he Sabina’ s father? Is he Jung?), the young woman looking out into a lighted area, the darkness that looms behind the woman.

There are new ideas here too. Sabina seems trapped here. What should be simply the edge of the box seats over which she looks to see the theater action below appears as a thick wall that pens her in. The man is more her keeper than her play going companion. Sabina here seems on the wrong and worrisome side of things.

And there is the color in the painting. When I read what Sabina wrote and what others have written about her, I see her world in black and white, maybe occasionally some grey and brown, but mostly black and white. So, how is it that this colorful painting speaks to me of her? I think it is because that yellow is a pretty scary color. That color says that, in this world, something is dreadfully wrong or about to be dreadfully wrong. The color reflects the fear and worry in Sabina’s face and the premonitions she carried in her head and heart.

Also a contemporary of Sabina’s was the German painter, printmaker, and sculptor, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938). This is his 1911 painting, Russian Dancer Mela.

What does this image allow me to write about Sabina? It is highly doubtful that Sabina ever danced in this way or that she ever wore anything like this costume. Nonetheless, there is something about the aloneness of this figure that I connect with the way Sabina was in all of the settings of her life. She is out there, on the stage, all by herself. Also, there is a drive and determination in this woman’s presentation that I think Sabina had. She is out there, on the stage, working very, very hard. And she looks right at us as she does her work. As I wrote in the prior blog about images of Sabina, we seem to have only two images of her as an adult. The two are fuzzy but in both, we see her looking directly at us. In the look, she seems to be saying that important line that she wrote about herself: “I too was once a human being. My name was Sabina Spielrein.” Not only does she look at us directly, she looked at hard work, loss, disappointment, and death directly.

The final artist who helped me imagine Sabina more fully than the available photographs was a surprise. At an exhibit of a contemporary Japanese artist that I went to simply to learn more about how current artists use traditional Japanese painting techniques, I was stopped in my tracks by this very large painting done in 2011.

The artist, Eri Iwasaki, calls this Rain Clouds. A woman holds her head above the weather. Sabina is the central figure. She holds her head above all of the interpersonal, professional, societal, cultural, and political “rains” that fall around her. At their most extreme, those rains include the Nazis who in 1942 massacred the Jews of Rostov-on-Don in Russia. Sabina and her two daughters were among the at least 13,000 Jews shot and thrown into mass graves on that one day. The darkness in her life is not simply to her right, to her left, behind her, and below her. It falls down upon her.

In this image, Sabina does not look directly out at us. She looks to her left, over and beyond us. Maybe there, she sees possibilities and opportunities. We need follow her sight line and the work that she left behind to discover what hope she might have seen.

Iwasaki says about this piece: “We all change constantly in response to the environment where we find ourselves...swayed by the state of our mind and heart. Depending on the nature of that heart, our meager existence can inspire great hope.” I think Sabina Spielrein had one of those hearts.